Impacts of Right-to-Work Laws on Unionization and Wages

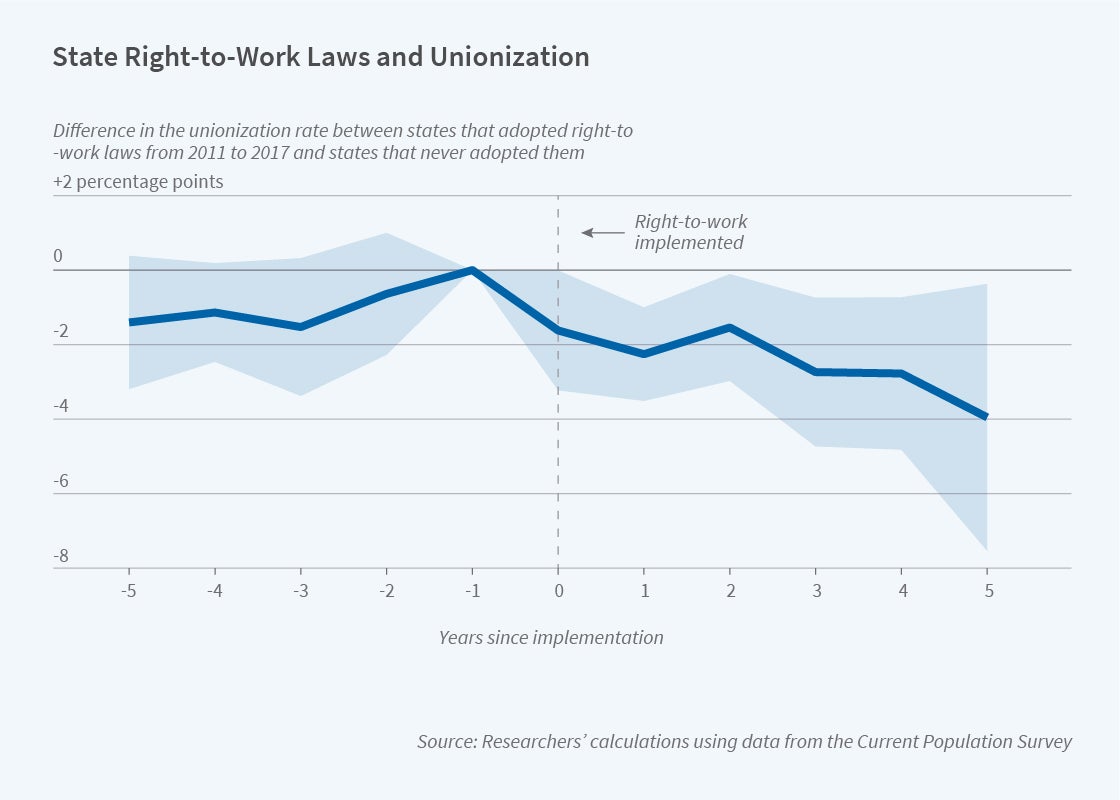

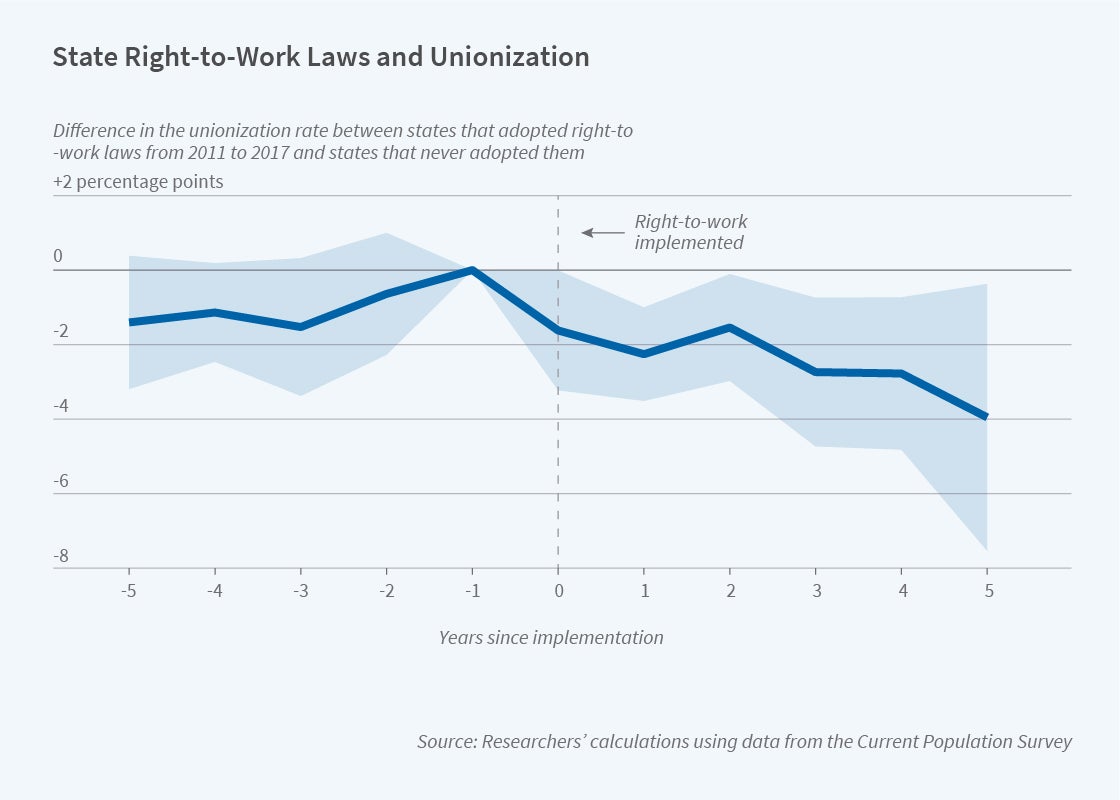

2011 to 2017 and states that never adopted them, relative to the year before right-to-work was implemented. The y-axis ranges from -8 to 2 percentage points, and the x-axis ranges from five years before to five years after right-to-work implementation. In the year of implementation, right-to-work reduces the unionization rate by 1.7 percentage points. The difference increases to 4 percentage points five years after adoption. Source: Researchers" width="1120" height="800" />

2011 to 2017 and states that never adopted them, relative to the year before right-to-work was implemented. The y-axis ranges from -8 to 2 percentage points, and the x-axis ranges from five years before to five years after right-to-work implementation. In the year of implementation, right-to-work reduces the unionization rate by 1.7 percentage points. The difference increases to 4 percentage points five years after adoption. Source: Researchers" width="1120" height="800" />

U nder the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, all workers covered by collective-bargaining agreements receive the full benefits of those agreements, such as wages and grievance redress, whether they are union members or not. In keeping with this approach, in most US states all covered workers must pay union dues regardless of union membership.

However, the Labor Management Relations Act of 1947, better known as the Taft-Hartley Act, allowed states to introduce “right-to-work” laws under which covered workers cannot be legally required to pay union dues. These laws can create a “free-rider” problem in union membership, undermining unions’ financing and ability to organize workers. Some states passed right-to-work laws before 1980. Six additional states have adopted these provisions since 2001. In Right-to-Work Laws, Unionization, and Wage Setting (NBER Working Paper 30098), Nicole Fortin , Thomas Lemieux , and Neil Lloyd find that these laws significantly reduce unionization rates and wages.

In the five states that adopted right-to-work laws in 2011–17, unionization and wages both declined, particularly in construction, education, and public administration.

They first test the impacts of right-to-work laws using data from five states — Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, West Virginia, and Kentucky — between 2011 and 2017. They use worker-level data from the Current Population Survey to test for differential trends in a state’s wage and unionization rates in the years after it adopted a right-to-work law, relative to states that had never done so.

Using this event-study design, the researchers find that right-to-work laws are associated with a drop of about 4 percentage points in unionization rates five years after adoption, as well as a wage drop of about 1 percent. These impacts are almost entirely driven by three industries with high unionization rates at baseline — construction, education, and public administration — where right-to-work laws reduce unionization by almost 13 percentage points and wages by more than 4 percent, again over five years. The impact of right-to-work laws on wages and unionization rates is also larger for women and public-sector workers, two groups that are overrepresented in highly unionized industries.

The researchers complement these results with a second approach based on the differential effects of right-to-work laws on the highly unionized industries. This strategy rests on the assumption that without right-to-work laws all states would have the same relative distribution of unionization rates and wage levels across industries. They estimate the impacts of these laws by testing whether right-to-work states have especially low unionization rates and wages in highly unionized industries. They find a difference of nearly 20 percent in the unionization rate between states with and without right-to-work laws. Right-to-work laws are also associated with 7.5 percent lower wages.

Finally, the researchers use both of these empirical strategies to examine a key labor-market question: how does unionization affect workers’ wages? If right-to-work laws only affect wages by lowering unionization rates, the causal effects of unions on wages can be estimated by dividing the effects of right-to-work laws on wages by their effects on unionization. Under this assumption, unionization appears to raise wages by approximately 40 percent.

2011 to 2017 and states that never adopted them, relative to the year before right-to-work was implemented. The y-axis ranges from -8 to 2 percentage points, and the x-axis ranges from five years before to five years after right-to-work implementation. In the year of implementation, right-to-work reduces the unionization rate by 1.7 percentage points. The difference increases to 4 percentage points five years after adoption. Source: Researchers" width="1120" height="800" />

2011 to 2017 and states that never adopted them, relative to the year before right-to-work was implemented. The y-axis ranges from -8 to 2 percentage points, and the x-axis ranges from five years before to five years after right-to-work implementation. In the year of implementation, right-to-work reduces the unionization rate by 1.7 percentage points. The difference increases to 4 percentage points five years after adoption. Source: Researchers" width="1120" height="800" />